It's baaccckkk ...

Not that CWD ever really left

CWD impacts people who rely on cervids for food and as part of their culture and as the disease spreads, First Nations are increasingly worried about its impact on food security.

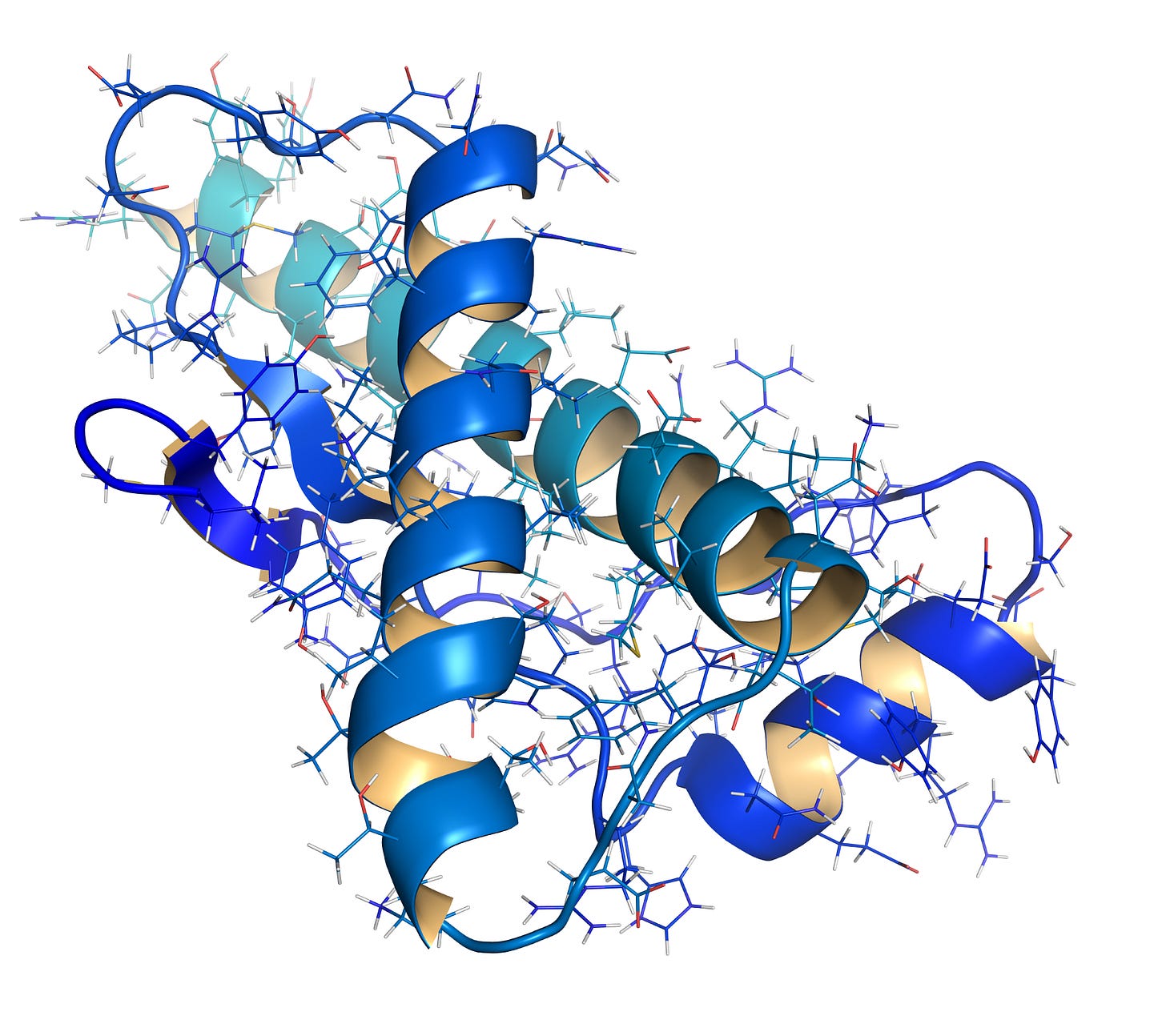

Chronic wasting disease or CWD is an infectious, contagious disease affecting deer, elk and moose (known as cervids). It is a prion disease which affects the brain when a normal protein is misfolded into an abnormal form, resulting in neurodegeneration. All prion diseases, including human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and cattle Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE, or ‘mad cow’) share long incubation periods which means that, for deer, it can take 2 years or more from the time an animal is infected until it dies from the disease. Diagnosis is difficult as animals tend to look and act healthy during infection, and conclusive testing can only be performed after the deer has died.

CWD was first identified in Colorado and Wyoming in the 1960s and recognized as a prion disease in the early 1980s. It has since spread to deer, elk and moose populations in 25 US states and 3 Canadian provinces, to South Korea via the import of elk from Canada and to reindeer and moose in Norway, Finland and Sweden. The geographic spread is due to both natural movements of deer, elk and moose as well as transport of undiagnosed animals to other regions.

The latest numbers for 2024 in British Columbia and Manitoba have increased that concern – a concern felt by governments as well. BC brought in new regulations and Manitoba is considering its own next steps in managing the problem. The biggest concern is that the number of cases are simply not going down.

Transmission of CWD may occur between animals or indirectly via the environment. Unlike many other prion diseases, such as BSE, the infectious agent is shed into the environment through saliva, feces and urine. Prions are exceedingly difficult to inactivate and can survive in the environment for 10 years or more.

The latest numbers for 2024 in British Columbia and Manitoba have increased that concern – a concern felt by governments as well.

Researchers have found that these prions can bind with soil, leaving them infectious but difficult to detect. There is no cure for the disease, so the focus has been on developing tools for detecting environmental CWD and diagnostic techniques for living animals. This work generally relies on cutting-edge ‘omics technologies targeting disease-specific biomarkers (biological indicators of disease). This will help wildlife management bodies remove and isolate infected animals and reduce potential spread in a population. Until these new tools are brought I to play however surveillance programs rely heavily on hunters submitting deer heads for testing and inspection.

Although there is currently no evidence of transmission into the human population, there are concerns that may change because prion diseases are poorly understood.

So far, no one is hitting the panic button but the steady rise in cases is concerning and vigilance, surveillance, and regulations are key to managing the problem.